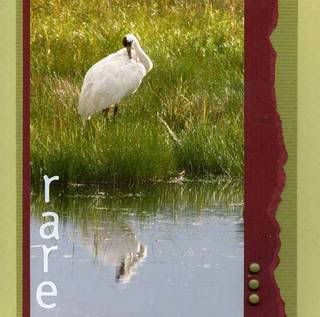

Storytelling is for the birds

One of the "first couple" of the Eastern Partnership Crane Reintroduction, the pair who successfully hatched a wild bred chick in 2006

As I write, there are literally hundreds of finches, juncos, Downy Woodpeckers and a couple Cardinals flocking to my feeders. I'm taking a break from the grueling shoveling of over a foot of snow that fell last night, you see, and the birds are seeking food wherever they can. I've even set out another feeder to try and reduce some of the fighting. I love watching the birds. I even love the harsh drama of nature, the one that involves the Cooper's Hawk I saw earlier, attracted by all the small bird activity in my yard.

I have a whole blog devoted to my escapades in birding. I continue to create small scrapbook pages celebrating some of my sightings I've captured on film. Should it come as any surprise, then, that I am always working on developing my repertoire of stories about birds? About this time last year, I wrote of my "world premiere" of an original porquoi story I created about Red-Winged Blackbird.

In choosing or creating these stories, I'm always looking for one key element; a bit of reality. Of course fantasy is part of the formula. What draws us into any story is that sense of "otherworld," of being taken to a different plane of existence. Even when a story shared is based on real events, a bit of magic occurs during the telling. When the story is well-told, time stops for both teller and listener. How else can you explain that surprise when the spell is broken and everyone says, "Oh my, it's been 20 minutes since you started?"

Talking birds, birds that have their colors changed through metaphysical acts, these are all part and parcel of the stories I choose, as long as they help to illustrate the real-life behavior of the avian protagonists. Last summer, I had the privilege of taking a week-long teacher workshop at Trees for Tomorrow called "Birding by Habitat," taught by Harriet Irwin. What's not to love? I spent the whole week in the north woods, seeking out birds in a variety of habitats and then talking about ways to infuse the school curriculum with birding knowledge. One class requirement was the creation of a project of our own choosing that we could actually implement in our classrooms. I chose to develop a program of birding stories to illustrate different aspects of bird behavior. This was not as easy as it might sound. I still haven't found or created a migration story that meets my criteria, but I do have a series of tales for other aspects of bird life. I've already had several opportunities to tell my Red-Winged Blackbird story, which explains territorial behavior during nesting. It even gives the listeners a little lesson in bird calls, as I've practiced long and hard to recreate the call of the blackbird as best I can!

I tell these stories in my classroom, of course, at any opportunity I can. These opportunities may not even be during science or environmental activites. Not too long ago, I told my version of "Eagle and Hermit Thrush," in which the little thrush obtains the prettiest song through trickery, thus explaining why we are more likely to hear his song than see his face. He's hiding from Eagle, you see, a bit ashamed of his cheating. As I told the story and Hermit Thrush began to sing as he fluttered down from the sky, I played the song on my BirdPod, so the children would hear it for themselves. They went on to do an activity that involved reading and following directions to make their own Hermit Thrush from paper.

What I did was what some are calling "environmental stealth storytelling." We don't step onto our venue proclaiming that we are edifying the world for the betterment of our environment. Instead, we share our stories and allow them to speak for themselves...as well as for the natural world. When I told the Eagle and Thrush story, the children had already entered the spell, waiting to hear what would happen. When the enchanting song of the thrush was added into the telling, those children were given an auditory memory that they might match at some point next summer, camping in Door County with their families. When that happens, it's my hope they'll say, "Hey Mom and Dad, I just heard the Hermit Thrush. Do you know why he hides all the time?" When our children form connections with the natural world, when they can identify and name what they see, hear, feel and smell, they give it value. These children will grow up one day, and it's my small hope that by naming these things and valuing them, they'll do what's needed to save that which has worth.